Over the weekend there was some serious butt-hurt on the Interwebs and the MSM about statements made by Chris Hayes during a Sunday show on MSNBC. Basically it boils down to this statement:

“Why do I feel so [uncomfortable] about the word “hero”? I feel comfortable—uncomfortable—about the word because it seems to me that it is so rhetorically proximate to justifications for more war.”

People were VERY quick to criticize him (and I’m not just talking about conservatives, quite a few liberals were angry too). The problem with this knee jerk reaction was that the majority of the critics formed their opinion without examining what he said in the context of the larger panel discussion and without Hayes’ qualifying remarks before and after the two sentences quoted above.

I wanted to record my perspective on what Hayes’ said and to look at how his critics reacted from both a macro and micro view because it’s important to who we are and who we want to be as a country.

First let’s start with the micro-view. I am descended from and related to many war “heroes”. I put “heroes” in quotes because hero is often a very subjective term depending on what side of a conflict you are on. It is also subjective because there are many that claim to be heroes but are not. Furthermore it is subjective because who we choose to anoint as heroes varies quite a lot. Let me give you some examples from my own family.

Through my paternal line I am descended from the union of Richard “Strongbow” de Clare and Eve MacMurchada (Aoifa Mac Murchadha)1 in 1168/69. The marriage was arranged between her father, the Lord of Leinster–Diarmit Mac Murchadha, as a means to lure Richard and his troops to Ireland to fight on Diarmit’s behalf against Ireland’s High King2.

Now if your people were English, particularly of Norman descent and/or associated with the court of King Henry II, you would consider Richard a hero. He was the first British military leader to take English troops to Ireland that actually managed to maintain power over a sustained period of time. If, however, your people were the native Celts, you would see Richard as an interloper, and not a hero (his marriage to Aoifa notwithstanding). Indeed, Richard settling in the Dublin area with his troops is pretty much recognized as the beginning of the end for Ireland’s independence3.

So, yeah, hero is a very subjective term. However, one could argue ‘but that was then and this is now’ and “Hayes is an American, not some foreigner passing judgement on American power’ and ‘he should be on our side’4. Yes, those are good points. So let’s look at some more recent American heroes from my family.

An Irish ancestor from my maternal line, Michael William Shanahan, stood up at the Battle of Shiloh and rallied his troops to charge up a steep ravine to push through the last of the enemy and overrun their encampments after an already long day of fighting. He was later promoted to be a first lieutenant by the popular vote of his company. He fought for almost the entire length of the war and managed to marry and father my great-grandmother after the Civil war was over. He died young, however, from tuberculosis that we believe he contracted during the War. So, was he a hero? In a literal sense, absolutely. He exhibited courage and he was admired for his brave deeds.

Would it affect your view of him as a hero if you knew that he fought for the South? To many Americans, it would. If you’re a Confederacy Fetishist, then yes, he would be a hero. If you are descended from the freed slaves that would have remained slaves had the South won, then not so much. I am neither a supporter of the Southern Cause nor am I a descendant of slaves. I am, however, this man’s great-great granddaughter and to me, he was a hero. It boiled down to this–he was afraid but he fought anyway. He was sick but he fought anyway. He stood up to protect his home, not out of some ideal but out of a very practical understanding of what it means to have your home, your job, your food, your loved ones taken away or put in grave danger as a result of “foreign” soldiers5. That’s pragmatism, not idealism.

And by this definition, all of our soldiers who are in harms way6 would qualify as heroes. There’s only one problem. If you were to ask Michael if he was a hero, he would probably say no. We have quite a lot of writing by him and to him and it appears that he joined the Confederate Army because he didn’t think he had a choice. He felt that the Union Army was marching south into Tennessee toward his adopted home of Senatobia, Mississippi and that Army was a threat to the people and the town he had come to love. To him the Union Army was an invader and if you don’t stand up to invaders you get crushed. He wasn’t doing it for some ideal of State’s Rights or the concept of White Racial Superiority. He simply wanted to keep the South safe from a large hostile force of interlopers. So he wouldn’t consider himself a hero. Indeed, I never met a true hero that accepted that label. Have you? But again, how you perceive him as a hero depends on which side you support.

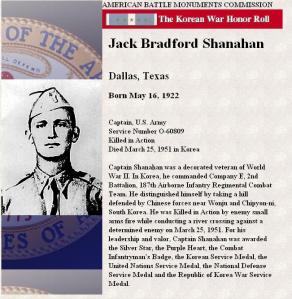

Speaking of true heroes, here’s the story of a more contemporary solider that went to his grave unknown by most of his countrymen. My family keeps his memory alive but he will receive no widespread accolades. My distant cousin, Jack B. Shanahan, is also a descendant of the same Civil War soldier, Michael, mentioned above. Jack was in the Army during World War II and part of the first forces to begin the offensive against Germany. He was twice captured by German troops7. He escaped at least once, maybe twice, from their encampments only to return to his unit and continue fighting. After returning to the U.S., he was briefly a civilian before re-enlisting. He next fought in Korea, where he was eventually killed by sniper fire8. His awards included: the Silver Star, the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

Was he a hero? Yes, absolutely. Not because he fought for something I believed in, but because he sacrificed himself again and again. Would he have called himself a hero? According to his children, and his fellow soldiers, both living and deceased–no. The truth is that when he joined the Army at the start of WWII he simply wanted to escape his alcoholic father’s house. When he escaped from the German POW Camp, he wanted to get back to his unit to be with his fellow soldiers and to help them. It was as much a wish to be useful and a desire to care for his men, than it was any high ideal. When he re-enlisted and went to war in Korea, he went, in large part, because he no longer knew how to live as a civilian and could not function outside of the military. Again, none of these motivations have anything to do with the high-minded ideals that we hear so frequently thrown into public discourse by slick tongued politicians who never served anyone or anything in their entire lives.

The point I am trying to make through my own family’s heroes, is that they didn’t consider themselves heroes even if their contemporaries, their government and their own family’s did. Why would they not? Humility? Maybe that’s part of it. But I think, it’s more a matter of actually understanding what it means to have gone to war. The sheer horror of it–the fear, the bloodiness, the godawful noise, the bonding with your fellow soldiers, and how that all feeds into and increases the soldier’s desire to ensure that future generations and the broader public never has to go through the horror of war themselves. Soldiers protect us in more ways than one. They don’t just physically stand between us and the enemy. They also stand between us and the loss of our peace of mind that comes with the exposure to war.

So how do we define heroes? By the time in which they fought ALONG WITH the cause for which they fought AND our relationship to that time and that cause. That sounds pretty damn subjective to me. That being said, how do we define and talk about heroes, such a subjective concept, in a national level? This brings me to the macro view. How often do you hear an honest, in-depth analysis of war and sacrifice coming out of the mouths of our leaders (even the ones that served, John McCain I am looking at you) or the MSM. Instead we hear a bunch of Jingoistic, happy horse-shit such as “bomb bomb Iran” and they will “greet us as liberators” and “mission accomplished”9.

Indeed the purpose of the panel discussion that Hayes held was an attempt to dig a little deeper than the normal jingoistic crap and move beyond the dick comparing nature of our national conversation regarding war. And it was done with the intention to pay homage to our fallen and injured soldiers. They were trying to REALLY acknowledge the sacrifices and what it SHOULD mean. Not what it DOES mean to the politicians and the propaganda machine, but what it SHOULD mean to each and every one of us who have not made that sacrifice. Hayes wasn’t saying that he didn’t believe our soldiers weren’t heroes. He said he was uncomfortable using that term because it has been so much abused by those seeking power while pandering to voters’ patriotic feelings. He made a much more subtle argument than we normally hear. More to the point, Americans have been so dumbed down by the constant barrage of infotainment and shallow, bumper sticker politics, that subtle arguments are beyond our ken. Instead, we resort to knee jerk outrage–the bumper sticker response to bumper sticker arguments.

Our leaders and politicians are taking advantage of a psychological ploy. They are taking real people and labeling them with the title of hero. And in so doing, they make those individuals become a thing–they objectify them. The hero symbol is so much easier to focus on because it is mostly a positive construct. Focusing on a hero, instead of the real person lost, allows us to ignore the ugliness of war. It’s not as easy to ignore the real person that died. A real person leaves behind a grieving spouse, an orphaned child, a bereft parent, guilt ridden colleagues or a bewildered pet. The symbol of a hero has none of these. From this perspective, it’s no wonder that real heroes want no part of that label. They real hero understands that the misuse of the term means that only more young men and women will suffer and die.

Ultimately, I think Hayes was right and what he said wasn’t offensive. He didn’t denigrate soldiers as much as he did take to task the politicians, leaders and MSM that use those same soldiers as a means of manipulation. Hayes didn’t say that they don’t sacrifice and he did say that he would prefer that fewer soldiers have to make such sacrifices in future. To me, that is the ultimate patriotism–to care enough for our veterans, our heroes to never use them and not subject them to any more suffering in future unless absolutely necessary. If you can’t see that then you either have your head up your ass or you’ve been listening to too much drivel from the MSM. Dig deeper America because until you do you will not be truly honoring our fallen soldiers.

_______________

More info on the two heroes I wrote about today is below. There are others, who are just as much on my mind.

This is a copy of newspaper article from http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~shanahan/shanahan_stowaway.gif and picture from my sisters website at http://www.littlehouseantiques.com/

Jack B. Shanahan, Photo and text from http://www.abmc.gov/

____________________

Notes:

1. Eve is the English spelling, but the Gaelic original is Aoifa and note the different spelling on the last name….

2. Diarmit needed troops to fight against Turlough Mor O’Connor, the High King, who felt threatened by Diarmit’s power and ambition. The full story is much more complicated than this but for brevity’s sake, this is pretty much the sum of it.

3. The introduction of Richard and his troops was a critical junction in Ireland’s history. Diarmit was despised, even up into modern times, because of his role in bringing the foreigners. In fact, he was labeled “Diarmait na nGall” or Diarmait of the Foreigners, thereafter. It took another 800 years for the Irish to push the English out in 1919 with the birth of the Irish Republic, which sadly only lasted three years before England once again took control of the island via Ireland’s acquiescence to being governed by the English constitutional monarchy, calling itself, ironically enough, the Irish Free State.

4. Unfortunately, too many conservatives in the US impugn the patriotism of Liberals and that also played a part in the condemnation of Hayes. For them, it was just another reason to affirm their mistaken belief that people who are generally against war are not patriotic, which any thinking person knows is idiotic, reductionist logic.

5. Surely his experiences as a young man in Ireland affected his opinion of invading armies and governments far away suddenly intruding into the lives of their less fortunate subjects. You have to remember that the Great Famine in Ireland was not simply the result of the potato blight but as a result of England literally taking away all other food sources in order to feed people in England leaving nothing behind for the native Irish to eat but potatoes. Once the potatoes failed, then they were clearly screwed. And the British Army continued to take Irish livestock, wheat and grain, fisheries, etc. There was food to be had, but it was taken by force and shipped to England.

6. Note that there are a lot of soldiers who are never at risk and never would be. For instance George W. Bush and his high-flying days as a member of the National Guard occasionally flying planes in Florida and often skipping his one weekend a month duty. That’s definitely not the definition a hero. You may also note that I never served in the US military but it wasn’t for lack of trying. I was nominated to go to the Naval Academy at 16 but they chose some rich fat boy instead. I later won a 3-year Army ROTC scholarship during my sophomore year at college but was never given the funds because I was deathly allergic to bees (even though they knew that before they gave me the scholarship). So I tried my best and had I been successful I would have served in the first Gulf War, the invasion of Panama, and probably the second invasion of Iraq (as well as a bunch of other combat missions that the average American has conveniently forgotten).

7. The family has two journals that were written during his POW days and which survived to be brought back to the U.S. We know that one of the POW camps he was held in was Hammelburg, Germany.

8. Family members and, I think, his fellow soldiers confirmed that it was sniper fire but the online records indicate only small weapons fire

9. So what do we call the thousands of soldiers who died in the many years after Bush gave that idiotic speech about the mission being accomplished in 2003? I’m not saying they weren’t heroes because their death came after his speech. I am saying that I’m offended that he had the nerve to praise our military while giving that stupid speech. Politicians that call the fallen heroes while at the same time blithely putting more soldiers into harms way, should have their tongue cut out. Congratulations, President Bush! You made America feel good about itself for all of five minutes before the next body bad arrived home and they kept on coming home for the next 7 years.

Very thought-provoking post and so true. I agree the word “hero” is used too lightly.

“Focusing on a hero, instead of the real person lost, allows us to ignore the ugliness of war.” So insightful, Tina. Reminds me why I like reading your blog so much. 🙂

And on a much more superficial note–how awesomely cool that you have all this information on your ancestors–going all the way back to the Middle Ages yet! When are you going to write a book about it? 🙂

Thank you for such positive feedback. I really struggled to not get too verbose on this one.

I actually started doing genealogical research when I was 14 but never had enough time to go much further. It was my oldest sister who, over the last decade, has uncovered so much of this really old genealogy. She found records of our ancestors selling slaves in SC and Georgia, the story of our family from Dublin, and even a connection to one of King Henry II’s bastard sons (he actually had quite a few bastards so it’s nothing incredibly exciting except that it’s such an old connection). In the end unless your family as a special heritage of notoriety, ie, nobility or fabulous wealth, most people only can go as far back as the Middle Ages because that was when the average person (at least in Europe) began to use last names. Before that they were James the Smith, George Son of Tom, or Sally of the clearing in the woods, etc. Also this is when paper became more available and there was an increasing number of people who could write, so record keeping became more and more common. To go back any further than that, I have had to rely on DNA. And I am getting too long winded again. 🙂

In re a book…I have always wanted to write a book about Michael Shanahan with my sister but she refuses to do so if I want to make a profit from it (which I would). I don’t feel right doing it without her since she deserves a lot of credit for all the research she has done. So that is a non-starter. In re to Strongbow, I am actually intimidated by how much work it would be as I would want to be as historically accurate as possible, even if it was just a fictional account based on the known story. I think a trip or multiple trips to England would be necessary. Not that I don’t love to travel…lol